- Your cart is empty

- Continue Shopping

How pandemic isolation is taking another toll on health-care workers

Neuroscience is only beginning to understand the power of physical contact from others

Reaching out with a reassuring hug or touch of a hand is a natural part of Sasha Adler’s job as a geriatric social worker.

Adler specializes in elder care, visiting clients and their families in their homes in Toronto. She says there’s an empathy communicated through touch that just can’t be expressed through words.

“It’s just something that naturally happens,” said Adler. “When people are vigilling … people will touch each other at the back of their necks … this sort of reassuring, acknowledging touching.”

The past two years of physical distancing measures disrupted the kind of care she and other care workers are able to extend. Much of her care is done at a distance through video conferencing. When she is offering it in person, she’s following all safety distancing measures.

“Usually I would touch the family members as well,” said Adler. “Not being able to do that … is a whole form of communication that’s gone. There’s a comforting touch that is needed at that time. I ached a little bit not being able to do it.”

For those like Adler whose work involves touching others, the pandemic has brought into sharp focus the quiet impact of touch deprivation.

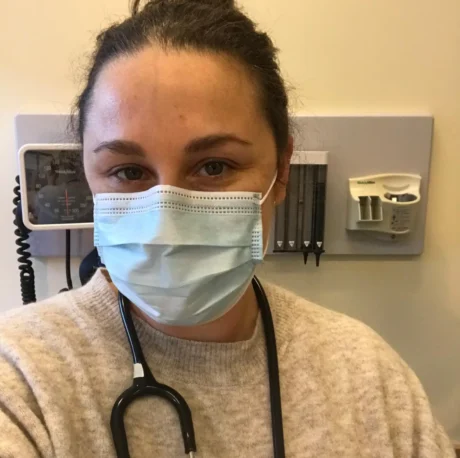

As a community health nurse working in Toronto’s shelter system throughout the pandemic, Melanie Spence is in constant physical contact with patients.

“But if we’re talking about touch in a context that’s meaningful for me personally, then it has been very absent,” said Spence.

Front-line health-care workers working in close physical contact with patients are increasingly prone to “severe burnout,” defined by the Ontario Science Table COVID-19 advisory board as “emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and diminished professional achievement.”

LISTEN | The emotional and neurological impact of touch deprivation:

A report published by the Ontario Science Table published in October 2021 showed that prior to the pandemic, 20 per cent of nurses were experiencing “severe burnout.” By spring 2021, more than 60 per cent of nurses were experiencing severe burnout. Much of this is attributed to long shifts, unpredictable overtime, staffing shortages and low morale.

Trudy Rudge, a nursing professor at the University of Sydney in Australia, says that within the health-care system, nurses aren’t encouraged to self-reflect and address their own emotional and physical needs.

“[Nurses] are right to feel that this is sending them to burnout,” said Rudge. “With burnout, you lose empathy, and without that communication of touch, you lose empathy. Empathy is the thing that actually underlines what happens when you get burnt out.”

The power of social touch

Neuroscientists are just beginning to understand the impact of touch from others and what happens when it’s disrupted.

“The social aspect [of touch] has really not received so much attention in research at all,” says neuroscientist Rebecca Böhme, director of the Böhme Lab at Linköping University in Sweden.

She and her colleagues found the sensation that comes from social touch activates significantly more areas of the brain than sensation from self touch.

“If you touch yourself, the brain can basically predict what this is going to feel like. And therefore you might not have as much of a response,” said Böhme.

When she and her colleagues used an MRI to measure the differences in brain activation between social touch and self touch, she was surprised by the contrast.

“[For self touch], it was a deactivation in a bunch of areas.”

Helping patients

Over the past few decades, researchers have observed how touch can help patients with certain medical conditions.

The Touch Research Institute at the University of Miami’s school of medicine has conducted more than 80 studies showing how touch can accelerate recovery since it was founded in 1992.

One study showed that premature infants who were massaged three times a day for 15 minutes experienced greater weight gain, alertness and were able to be discharged from hospital an average of six days earlier than the infants in the control group.

“What happens is that when you move the skin, you’re stimulating pressure receptors under the skin, and those pressure receptors send a message to the brain,” said Tiffany Field, founder and director of the institute.

“The brain has 12 cranial nerves, and one of them is called the vagus. And it is the largest nerve in that it has more branches to the body, to different parts of the body, than any other nerve in the brain.

“So what it does is it slows down the heart … your blood pressure slows down and [that] slows the release of stress hormones.”

Simulating the benefits

Even during pandemic times of isolation, there are ways to simulate some of the benefits of social touch, according to Jacques MoraMarco, a practitioner of Chinese medicine and academic dean of Emperor’s College in Santa Monica, Calif.

“One thing that [you] can certainly do is auto massage, self massage; stimulating the acupuncture points,” said MoraMarco.

“So if you cannot go and get a massage, or get that therapeutic touch, you can actually stimulate some of these points yourself.

“Of course, the human touch and to have the ability to hug somebody and … to be close to relatives and loved ones … we cannot replace that.”