- Your cart is empty

- Continue Shopping

‘More harm than good’: Academics sign letter condemning Quebec curfew

MONTREAL — In a letter to the Quebec government published Sunday, a group of 13 specialists made their demand clear: no more curfew.

“Will the government continue to pull Quebec apart from the rest of Canada every winter by prohibiting the free circulation of people when it gets dark?” the letter reads.

The letter was signed by a medley of specialists, ranging from sociologists to legal experts.

The authors of the letter argue that, based on data from 2020 and 2021, last year’s curfew did not play a significant role in slowing the spread of COVID-19

In 2021, the provincial government issued a curfew that began in January — during the peak of the second wave — and ended in May. During this time, the overall number of daily COVID cases dropped considerably.

“Observational studies show that [the curfew] was useful in preventing travel and gatherings at a time when the number of cases in the general population remained high,” the Quebec health ministry (MSSS) said in statement Friday.

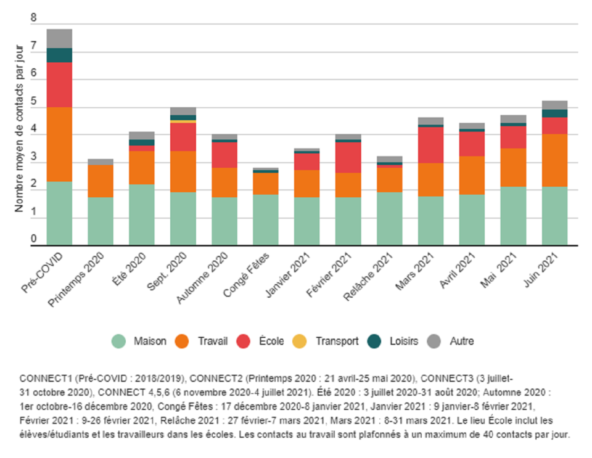

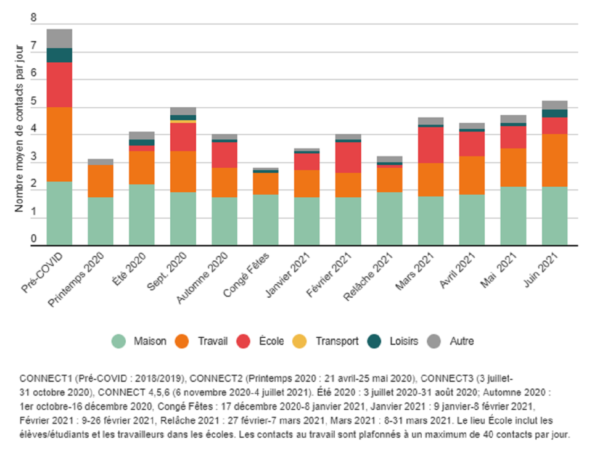

But according to a study titled “CONNECT,” conducted by Quebec’s public health institute (INSPQ), the degree of social gatherings in the home remained relatively consistent both before and after the curfew was put in place.

In November of 2020, for example, the average number of an individual’s daily household contacts was 1.7. This number increased slightly in December to 1.8, and fell back to 1.7 for the months of January, February, and March.

Citing this data, the letter authors state that although the curfew may be correlated with a decline in cases, it is not necessarily the cause of this decline.

“The government has never demonstrated the efficiency of the curfew. Instead, it carefully avoided discussing numbers, rather using a confirmation bias sophism: the curfew worked because the number of cases dwindled or less people went outside during the night.”

WHAT DOES THE RESEARCH SAY?

Although studies on the efficacy of curfews are sparse, research from France seems to suggest that curfews are correlated with the slowing of the virus, even when lockdown measures such as closing bars and restaurants aren’t in place.

The study, published on the pre-print server medRxiv, found that the spread of COVID-19 was slowed between Oct. 24 and Oct. 29, when 54 territories in France issued a curfew. Transmission was slowed even further beginning on Oct. 30, when the government implemented a nation-wide lockdown, which included shutting down non-essential businesses and banning private gatherings altogether.

Interestingly, the curfew was particularly effective in curbing the spread among those aged 60 and up, i.e. the more vulnerable population. In contrast, the youngest age group — age 0 to 19 — experienced fewer case numbers when the lockdown measures were implemented.

Although this information seems to suggest that a curfew can be an effective tool to combat COVID-19, the study authors point out that inconsistent COVID measures across France can complicate matters.

“We find that curfews have not necessarily been imposed in departements where acceleration [of the virus] was the largest, which makes conclusive comparisons of the effectiveness of COVID-19 measures harder to do,” it explains.

It should be noted that no similar research has been conducted in Quebec, although one study, also published on medRxiv, found that last year’s curfew did reduce nighttime mobility significantly. However, this study does not indicate whether this reduction is linked to fewer daily cases of the virus.

SIDE EFFECTS

In addition to questioning the efficacy of curfews, the letter also expressed concern for the emotional well-being of Quebecers, who may be suffering from “pandemic fatigue,” and for vulnerable groups such as homeless people and people with disabilities.

“The current collective effort to curtail the curve of the fifth wave will have to allow people to enjoy life in a way or another, with activities and walks in small groups in secure outdoor settings,” the authors state.

“Depriving [Quebecers] from the possibility of being outdoors in the evening and at night, after work or school, is a very bad idea, as it could encourage people to take risks indoors clandestinely.”

The MSSS has acknowledged studies representing the “negative impacts on lifestyle” that curfews can have, but did not specify what these impacts were.

“The advantages and disadvantages of all measures are assessed and the measures recommended by public health are based primarily on health considerations, in addition to managing risks and threats to the population,” reads a statement.

The MSSS has yet to respond to further requests for comment.

— With files from CTV News’ Rachel Lau.